In Search Of Lost Glory: Prost and Arnoux's fight for Martyrdom and dominance

In the history of sports, frenchmen have rarely been described as cold-blooded. And yet few podiums have ever felt colder than those shared between Alain Prost and René Arnoux.

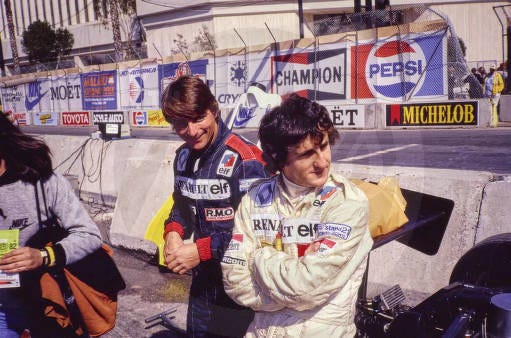

When Alain Prost joined Renault in 1981 as a fresh young driver, his teammate René Arnoux was already an experienced driver. So when Prost started winning more regularly, during a particularly frustrating stroke of bad luck for Arnoux, the rivalry between the frenchmen began. When Prost won his first race at the French GP in Dijon, something shifted in his mindset: no longer the young rookie, but a race-winning hero. He told himself “Before you thought you could do it, now you know you can.” And so the relationship between the two teammates began to deteriorate.

This animosity culminated in the French GP one year later held at Circuit Paul Ricard. Where the French victory with a one-two podium finish for Renault should by any means have been cause for celebration, the podium was less than a joyous occation. According to Prost, Arnoux had failed to comply with team orders, which stated that in the case of a one-two finish Arnoux would have to let Prost past to help him fight for his place in the driver’s championship. Despite his claim being supported by television footage, Arnoux denied knowing that any such orders had been given, but their relationship was shattered. Arnoux left Renault at the end of the season, and their rivalry persisted.

What didn’t help was that their friction soon became nationalised. In France, they were packaged as opposites: the ragtag, free and unpredictable Arnoux, and the cold and calculated “professor” Prost. Each race became a referendum on “Who’s the real French hero?” These public tensions especially affected Prost, who has through his entire profession believed himself to be unfairly treated by the public. “When I went to Renault the journalists wrote good things about me, but by 1982 I had become the bad guy. I think, to be honest, I had made the mistake of winning! The French don't really like winners. It's hard to explain, but the French prefer martyrs who lose gloriously.”

Of course Arnoux was fantastic at playing the martyr, with his hotblooded fighting spirit, and his intricate “frenchness”, for lack of better terms. More than that, he was likeable. And in French public opinion, Prost was whiny and calculating. In a world where Francois Cevert and even the French-Canadian Gilles Villeneuve had never ceased to steal french hearts, Prost was an outsider.

In interviews they dodged each other’s names or called each other out in interviews. On one occasion, Heinz Prüller stated that Arnoux spat at the picture of Prost in a french newspaper. Fans split camps. The media followed.

In a day and age where the influence of media has never seemed extensive, this story may pose a cautionary tale. Where fans and media have come to form an intrisic part of the sport, series like Drive to Survive have been able to thrive for their dramatic appeal rather than for their accuracy. For it shows that sometimes the narrative is imposed before the drivers can shape it. It wasn’t just Prost vs. Arnoux - it was ideology vs. instinct, image vs. authenticity, the associations of one nickname against another. F1 wasn’t just about who won. It was about who deserved to win.

And that’s what makes this old rivalry feel eerily modern.